Last updated on 14/02/2026

Depending on how you want to count, I’ve been roleplaying for over three decades now. Personally, I think the pretend games I was playing with my friends as a young child count, as we were adopting roles and negotiating what happened in a shared fiction. Even if you don’t count that, I got my first rules-based roleplaying system in the 90s, it was AD&D. Because Indiana does everything a decade behind the rest of the United States, this was just in time for the satanic panic around roleplaying games. That, however, is a story for another day.

More recently, during the pandemic and since, I’ve taken to playing solo RPGs. There are a couple of things that drove this for me:

- Scheduling with other adults is effectively impossible

- I want different things from my games than my friends

- I wanted to model a non-screen-based hobby for my kid

- It helps me learn systems I want to run

When I started about five years ago, I thought of solo tabletop as a starkly different beast than group roleplaying. What I’ve come to appreciate over my years playing them is that they really aren’t. All roleplaying games center around the notion that some number of people will negotiate a fiction and tell a story that they find enjoyable to tell and participate in. What I’ve recently realized is that central conceit doesn’t change when the number of people is one.

My thesis here is that, in tabletop roleplaying, group play isn’t binary. The rest of this essay argues the following points:

- that group play is a spectrum

- all games incorporate elements of group play and solo play

- Contention and Consensus are better lenses to think about play than Solo and Group

I think these points are interesting in their own right, but they’re also useful. By building shared language and understanding around how the rules of our games help us navigate conflict within our fiction and at our table, we can:

- Better design new systems to support us

- Build language to help express our wants and needs to others we play with

- Clearly discuss the differences between games and styles of play

Play is Nearly Everything

Before we talk at length about group play, we’re going to have to settle on a definition of play, and that’s always spicy. What is play? It may shock you to learn that play is a topic of serious academic debate. Dr. Stuart Brown describes play as a “…state of mind that one has when absorbed in an activity that provides enjoyment and a suspension of sense of time. And play is self-motivated so you want to do it again and again.” Perhaps closer to our hobby is Raph Koster of Ultima Online and Everquest Fame, says in the Theory of Fun, “Fun from games arises out of mastery. It arises out of comprehension. It is the act of solving puzzles that makes games fun. In other words, with games, learning is the drug.”

Note that none of these thinkers say that play is rolling dice, or moving figurines about a hex mat, or tracking the decrease in HP that happens as the result of an attack. Both, however, would argue that getting lost in a tactical combat scene and figuring how best to use your character’s abilities to navigate combat is play. They would also argue that a social conflict in a court setting and successfully roleplaying that scene is play. I particularly like Raph’s take because it aligns so well with the Powered by the Apocalypse philosophy “we play to learn what the story is.”

Critically, and perhaps surprisingly, both also appear to argue that much more of our games than the play sessions at the table or over discord, roll20, or whatever your tool of choice is are technically play. Reading the manual to better understand the rule system is a task that is absorbing, builds mastery, and is self motivated (unless you’ve got a very aggressive DM). Theory-crafting character builds and arguing on reddit about their merits also falls under the above definitions of play. Painting minis, sketching your character, preparing a campaign, these are all forms of play. Telling stories about past campaigns is play. In a very meta way, my writing this essay is a form of play. By most formally accepted definitions of play, almost any time we interact with the hobby, we are engaging in play.

Taxonomies Are Fun!

There are a lot of axes we could talk about TTRPGs on. Crunch vs. Rules-Lite. Fiction first or Rules first? Simulationist or narrative driven? Gritty pulp action, or slow burning court thriller? Grand adventures or character stories? The list is nearly infinite, as there are a great number of players and a larger number of games.

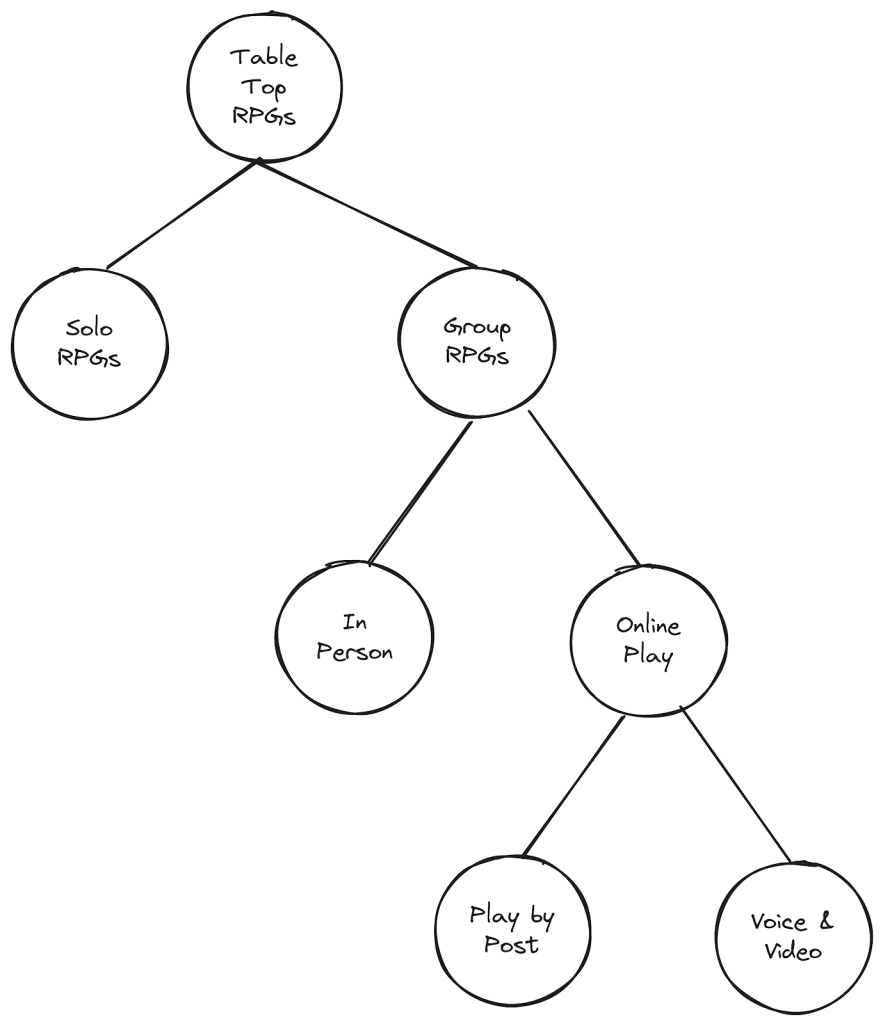

Since we’re focusing on group play, I want to look at the following taxonomy:

I feel like this taxonomy is a pretty safe one. It encompasses a huge percentage of the games we think of when someone says tabletop roleplaying games. Most people, inside and outside of the hobby, immediately jump to the notion of playing games in a group when they think of TTRPGs. I think that accurately describes the bulk of the market by item count and dollars spent, but solo games are important too.

I’ve further broken down the group RPGs based on how they’re played. Many games are played in person, around some shared physical space. However, technology has afforded a number of ways to play TTRPGs when we’re separated from the other players by vast distances. This we’ll call “Online Play”. I’ve further divided this group based on how the game is played. Using the internet as a collective shared space and playing as you would if you were in person using tools like Discord & Foundry VTT to support the game, or play-by-post games.

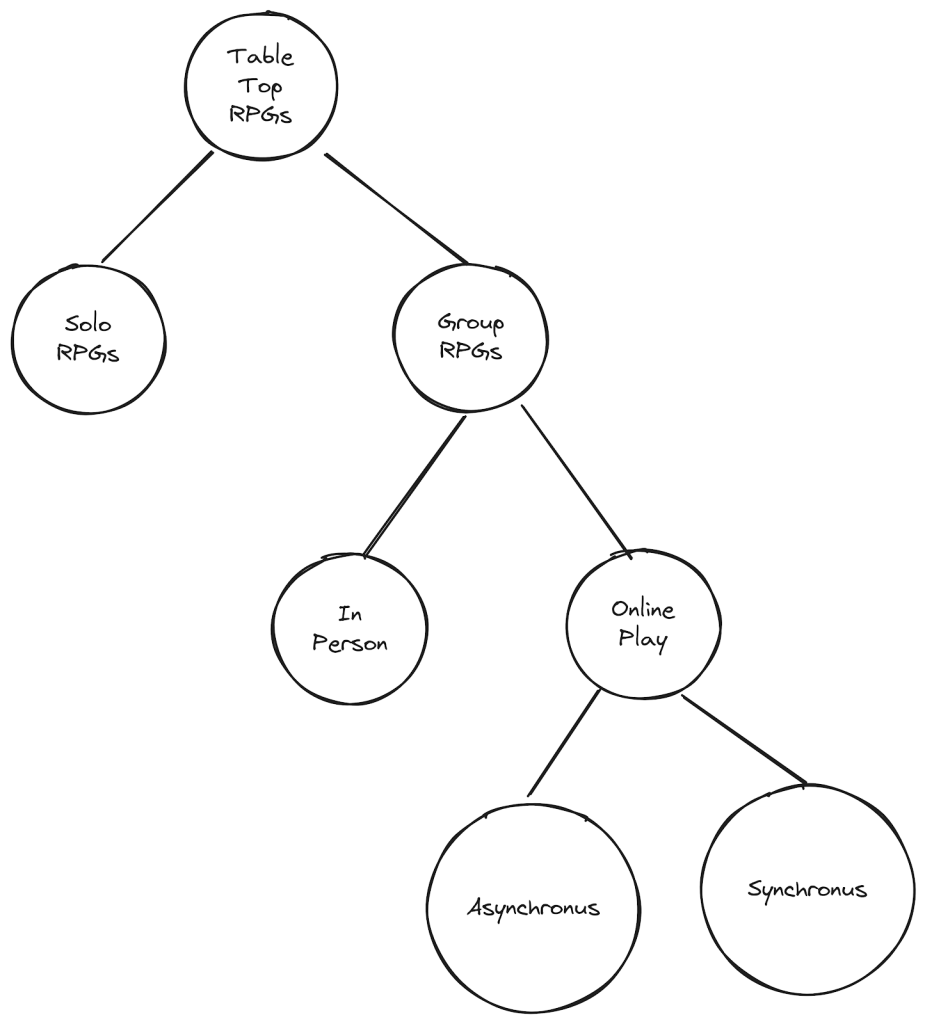

Why is it interesting to separate games played using voice and virtual tabletops where all the players are together interacting at the same time from play-by-post games, where players take turns as time allows, and where all players may not be present whenever someone is writing a message or post? Because the two types of play differ in how synchronous the action is. So, instead of saying play-by-post and voice & video, let’s call them what they are, synchronous play and asynchronous play.

But that feels weird, doesn’t it? If you’ve done play-by-post games, you’ll know that sometimes you’re more asynchronous than others. Sometimes several players will be “active” within a 15-30 minute period, and the game will make some forward progress, and then it will go quiet again for another 8 hours until people come home from work, or wake up from sleep.

Similarly, if you really feel that online play is truly synchronous, think about the last time three people spoke at the same time in your voice channel, and how easy it was to understand what was going on. Even around a physical table, where communication channels are richer, the game isn’t truly synchronous. Your paladin has initiative, what do they do? Shhhhhh, the DM is talking! You haven’t spoken in a while Steve, what would you like your character to do?

We have rules and social norms to negotiate turn taking and to decide who has agency in a given moment, and I think that’s really telling!

We’re Using the Wrong Words

Simply put, we’re using the wrong words here. Synchronous and asynchronous play are incorrect, because they can’t really tell us what kind of TTRPG we’re playing. Every game has aspects of asynchronous play and turn taking, so we can’t use that to discriminate them one from another. Similarly, “Group Play” lacks discriminative power.

“Group Play” Misses too Much

The highest level of our taxonomy may still feel good – solo RPGs and Group RPGs are fundamentally different experiences. But remember what we said about play above, play is (nearly) everything in our hobby.

It Doesn’t Incorporate Broad Definitions of Play

By that definition of play, I’m engaging in group play when I theory craft Shadowrun characters on reddit. I’m engaging in group play when I share stories about my current campaigns with my coworkers and friends. I’m engaging in group play when I write a solo-character scene in my play by post game (because there is a social expectation that the other players read it and use it in their fiction).

I want to consider the above example specifically. I suspect a lot of us have played Mines of Phandelver at some point. If you haven’t, think about the first commercial module your group ever ran, or the first time you played a convention game with your friends. Chances are, you’ve been in a setting where you’ve played a game in a group, and you’re aware of another group that’s run the same module.

Talking about what your group did, hearing about what their group did, and learning about the differences was fun, wasn’t it? It’s cool to hear about how other groups handle the same challenges! After all, the open nature of TTRPGs is a big part of what I find so exciting about the hobby. A group of humans have far more flexibility to react and negotiate their interactions than a computer can ever be programmed for.

That being said, group play, as we understood it in the original taxonomy, would only speak to the individual groups playing the module. It wouldn’t be understood to mean the various groups discussing their experience after the fact, which is a shame.

Group Play Lacks Discriminative Power

It’s not just that it fails to capture the above form of play, which might lie outside of what you consider to be playing within our hobby. Group play also lacks discriminative power within the TTRPG experiences we all agree are play. Let’s consider more coordinated forms of multiple group play: the competitive dungeon crawl, living world games, and west marches campaign.

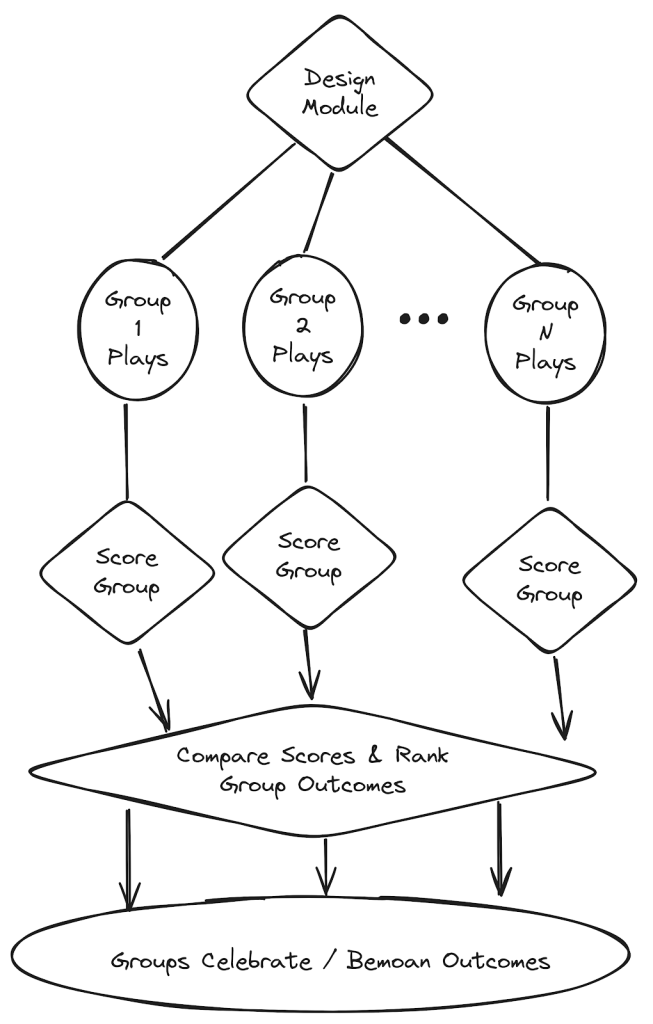

Competitive Dungeon Crawls

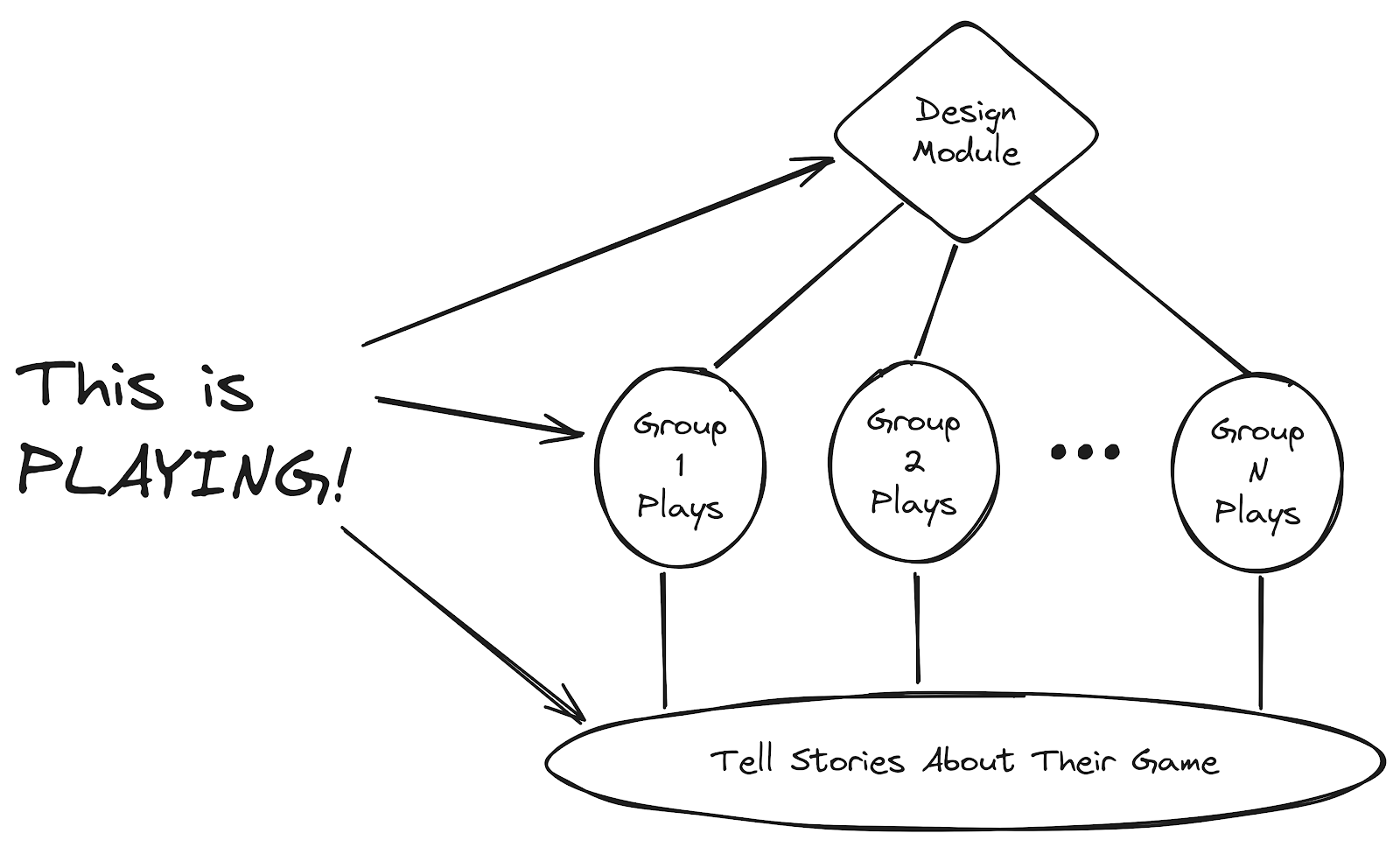

My first introduction to the heady world of competitive TTRPG play was at the second annual Dungeon Crawl Classics held at Gencon. I was a young man with a fistfull of generics and a dream to play literally any game I could find before my Vampire larp started that evening. It was a standard dungeon crawling affair, but we were scored based on how many monsters we defeated, how many puzzles we solved and how we solved them, and how much treasure we collected. Several tables all played the same module that day, and at the end of the day the scores were tallied and results were posted. The general flow of play is shown above.

I still have the second place trophy I won that year, and it’s still one of my fondest convention memories. Why? Because I had a blast. The module was fun to run, and the added competition between tables really helped me stay engaged with it as a player, even all these years later. Given that we were literally competing for fabulous prizes, like plastic trophies and source books, I think we have to accept that not only was the group at our table playing a game, but all of the groups together were collectively engaged in group play.

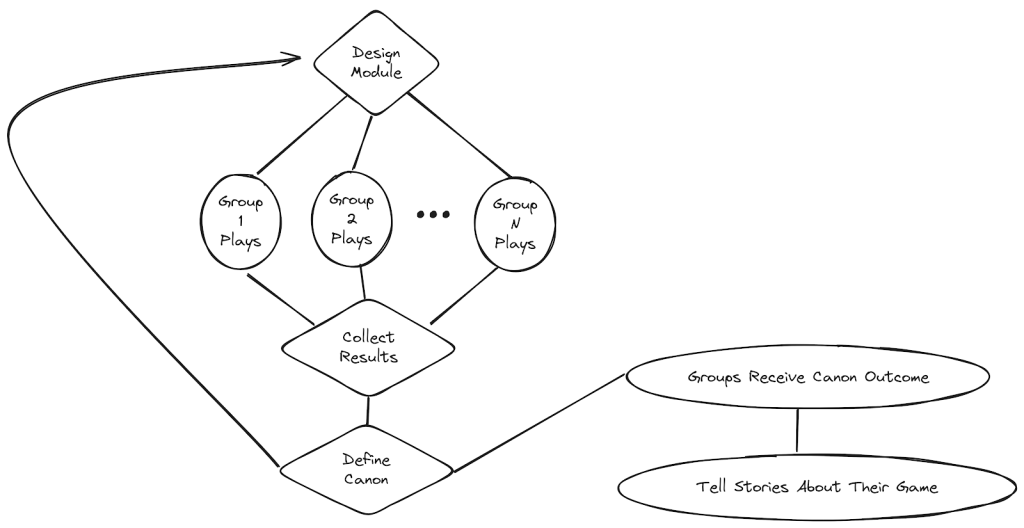

Living World Campaigns

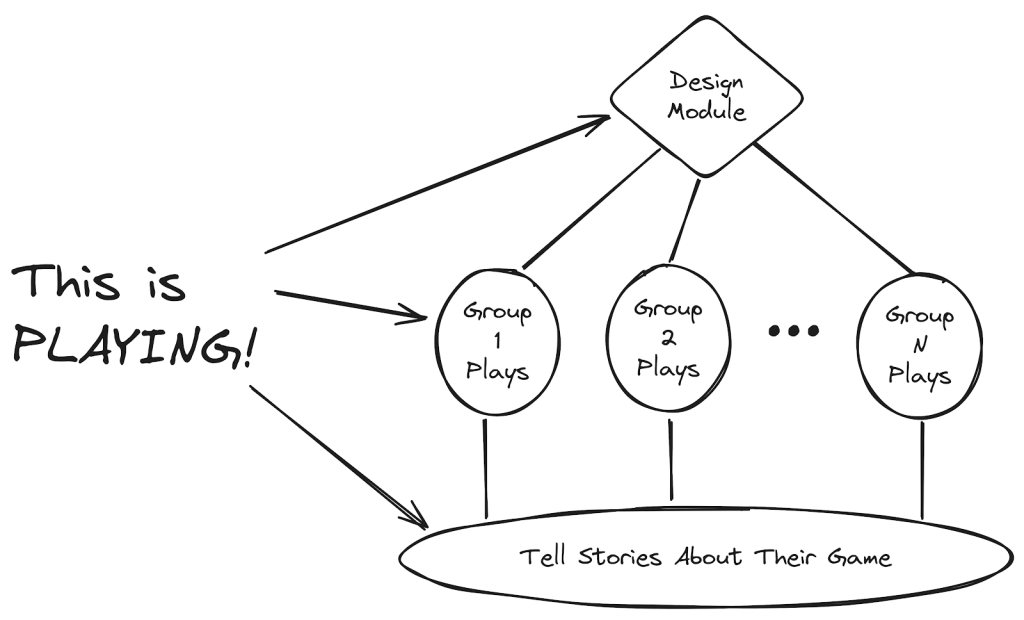

Living world campaigns are another type of large multigroup play. There are a number of potential organizing principles, but in general, they follow the flow shown in the above figure:

- Some group or council design a module that’s consistent with the current world canon

- Some group (typically the same one) act as DMs for a number of groups playing

- Could be at a convention

- Could be time-gated like DSA or Living Greyhawk

- Could be whatever Pathfinder Society is

- At the end of the module, results from all tables are collected

- The council decides on the new world cannon based on the tables’ collective results

- A new module is written and the cycle starts anew

As above in the competitive play example, it is obvious that there are multiple types of group play happening here. Certainly each table has a group playing a TTRPG in the traditional sense. The groups are also collectively forming a large group of player who collectively influence the world’s canon and potential directions of the next module. Finally the governing body that decides on canon and writes the next modules also form a distinct group of play. A simple term like group play fails to cleanly discriminate between these three distinct sets of play groups, some of which contain the same people!

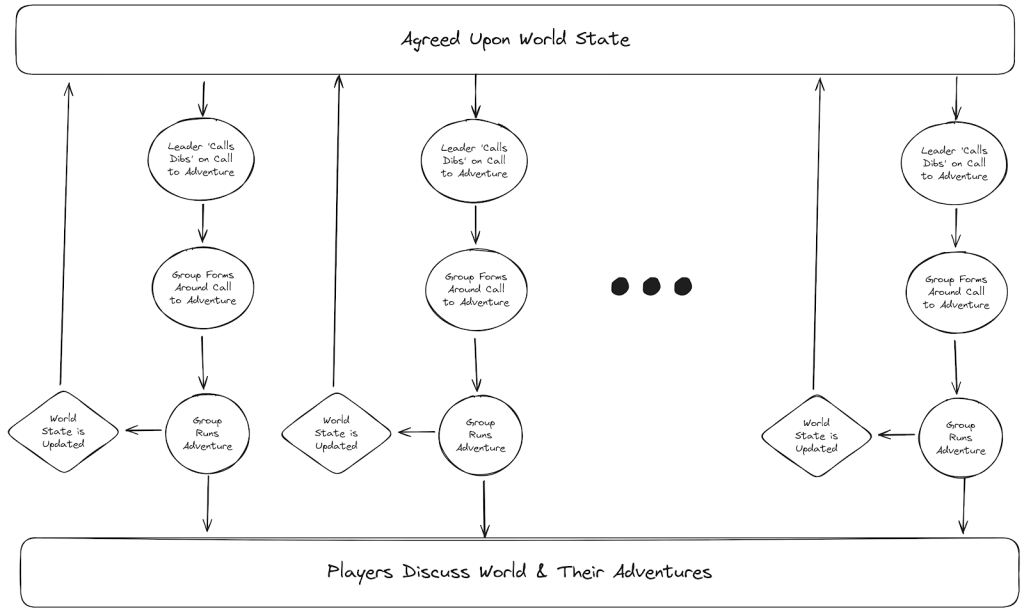

West Marches Campaigns

From the original blog post, west marches campaigns were conceived as quote:

- There was no regular time: every session was scheduled by the players on the fly.

- There was no regular party: each game had different players drawn from a pool of around 10-14 people.

- There was no regular plot: The players decided where to go and what to do. It was a sandbox game in the sense that’s now used to describe video games like Grand Theft Auto, minus the missions. There was no mysterious old man sending them on quests. No overarching plot, just an overarching environment.

Today, west marches style campaigns have evolved a bit, but much of the original flavor is still there! There is a diagram of the flow of play in the figure above. Modern west marches campaigns, especially in the play by post scene, also allow for multiple groups to run sessions simultaneously within the same world. So, not only are there a pool of players, but there are a pool of approved DMs, and all are waiting to form up a smaller group to interact with the world and drive its story forward in exciting ways.

Allowing for multiple concurrent-ish adventuring parties doesn’t actually change the behavior of a west marches game too much, so long as you take care to “stay out of each other’s way”. If one party walks north from the starting area, and another south, it’s unlikely they will interact with one another’s stories within the context of a single adventure. Now, how they change the game world should allow for groups to influence each other. If the adventure doesn’t change the fortunes of some of the world’s actors, or the state of the world itself in some measurable way, was it really an adventure?

Adventuring needs to have consequences. The multiple approved DMs in a west marches style game coordinate to make sure that those impacts to world state are communicated amongst all of the DMs and players so that they can all successfully play in the same world.

All Games Contain Elements of Individual & Group Play

Even with a single table with one DM, one set of players, and one module that no one will ever talk about outside of a single session, group play fails to capture the spirit of what is happening.

Most, if not all of us, have been at a table that struggled with players who back seat either the DM or another player’s actions in or out of combat. It’s one thing to remind a player that they have a healing potion or that they could help you flank an enemy, it’s another to insist they play a certain way and we can all tell when the line is being crossed.

Similarly, in play by post systems, it’s sometimes tempting to describe how another player or NPC experiences your player, but taking that agency away from the other player is called god modding, and it’s considered problematic by the community.

There are, of course, concessions to be made for speed of play and flow, but the thing that’s fundamentally at play is the idea that a player should have agency over how their character or characters act, and when they don’t, it feels bad. So, even in a group game, there’s a clear line being drawn around player agency, and that is necessarily an individual play concern: the individual player has agency in how their character behaves. They almost certainly don’t control the outcomes, at least not entirely, but they should be able to make the choices!

Ok, Yes, but What’s Your Point?

I think it’s inarguable that competitive dungeon crawls, west marches games, and living world campaigns are forms of group play. Further, the group that is playing these games is far larger than the party and DM at any individual table. Since group play fails to include things we recognize as play among multiple people, and fails to discriminate between types of play groups participate in in interesting ways, it’s not a good class. Further, all games have both individual play elements and group play elements. If they didn’t, we wouldn’t be so incensed by things like back-seating and god-modding. So, what are the right words?

Consensus and Contention Are the Right Words

I think that contention and consensus are the right words to describe what is going on in our games. As to why I think those are the correct words, here is what I think is really happening in our TTRPG games:

- There are moments of individual play that impact the group

- There are group actions that impact the individual

- The rules (and session 0) exist to negotiate those interactions

I know that’s boiling the ocean a bit – I’ve reduced a multi-million dollar industry and decades of thought and play into three bullet points, but it seems to be an apt, if parsimonious, description of play within our hobby. When we play, we’re trying to build a shared representation of the game. That’s the thing, writ large, that we’re trying to build consensus around. There’s also contention at the table. Specifically, there’s contention whenever two or more players can materially impact the other’s experience of the game.

Wherever we have a rule or a discussion about the game itself, it’s to help resolve these contentions and build consensus. This is true both directly, e.g. the rules and the dice say whether or not your character strikes their opponent with their weapon, and at a meta-level, e.g. the rules exist and resolve contention around how combat in the game works. It’s not just the rules of the TTRPG though. Lines and veils, session 0s setting tones and settings, two player negotiating backstories or connections to one another, these are all tools for building consensus between the relevant parties about the game is, both its state and how it is played.

Isn’t This Incredibly Up Its Own Asshole?

Oh god yes, unbelievably so. We’ve taken a lot of words to say that our ability to play games hinges on our ability to agree on what the state of the game is and how it is to be played. Critically though, we did so by looking at the differences between solo play and a variety of types of group play. Games don’t differentiate themselves on the presence or absence of groups and subgroups, not directly. Games are arrayed based on where contention exists, and how consensus is built.

In a solo game, at a minimum I have to build consensus with myself. How am I going to play the game? What are its rules? How closely do I need to adhere to canon events from previous sessions? What do I need to do to consider my game ‘done’? I can use external tools like Mythic or the GURPS manuals to help me build consensus for myself, and I can house-rule them into oblivion if I so care to. Once I know what I’m doing, I can proceed to structured play.

In group play, consensus plays the same role, it just has more concerned parties. If a player too frequently ignores the group consensus, they’ll end up excluded from play. If you’ve ever watched a group of five year-olds play pretend and seen them eject a kid for being too domineering, this is what’s at play. Similarly if you’ve ever been at a table that had to eject a problem player, if it wasn’t for reasons external to the game, it’s likely because they couldn’t agree on what the state of the game was or how it had to be played.

Why Do We Care About Consensus?

This is all really obvious stuff on a certain level. Yes, we have to agree about what the game is in order to play it. Yes, we have to agree on what the state of the game at any time is for a game to have meaningful interactions and outcomes. Yes, social gaming experiences require forming social norms and standard rules apply about enforcing those norms.

The thing is, that all matters. Building consensus about the game before we start is critical to allowing people to select in, and out, of the right games. People who know what they’re getting into tend to be more engaged with the game while it’s happening. Consensus before and during play helps prevent hurt feelings. We often talk about the system rules, and which supplements are in or out, and the convention codes of conduct, and safety tools, and table etiquette as if they’re separate things. They’re not; they’re all part of us negotiating how we play with one another.

But Outside of Decency and Having Repeat Players, Why Do We Care?

I don’t just want to rail on and on about the appropriateness of safety tools and community codes of conduct. There are reasons why contention and consensus are interesting to the game itself:

- The game cares about things with contention and consensus building

- Contention and consensus building can bottleneck or gate play

- Having rules to resolve contention and build consensus smooths and speeds play

So, effectively being aware of these things helps us play games at a better clip, with less downtime and waiting around, and it helps us identify what matters to a game, which should help us identify games that interest us.

Consensus / Contention Says What Matters

My favorite example of “consensus building rules tell us what matters in a game” is around sanity and morale mechanics. Consider the differences between Ravenloft and Call of Cthulhu for a second. All flavors (as far as I am aware) of CoC have a bespoke sanity mechanic, and many have relationship mechanics that can have really important impacts on character performance. For example, in Delta Green, a modern Cthulhu game, you can lean on your close friends to help you recover sanity, but it burdens the relationship (mechanically some number goes down). Strain the relationship enough (number is 0) and the relationship breaks. It’s cool narratively, it’s an interesting mechanical piece too. Do I lean on my most effective friend, or do I spread my emotional labor around?

Compare that to a D\&D Ravenloft campaign. Now, Ravenloft is no less a horror game than any CoC campaign. The characters are up against tough odds, the gods have turned their backs on you, and your beset by undead at every turn. The characters are hardened heroes, but even hardened heroes need aid to maintain their morale. It’s just that Ravenloft does not give a damn about that. There aren’t any mechanics for it. You don’t have mechanized relationships with NPCs that you can lean into for bonuses and recovery. Rules as written, the system doesn’t care about your brother Tim back home, and how you’re striving so he can live a better life or whatever. It might matter to your player, the GM can opt to bring it in, or any other player could bring it up in their play, but they aren’t obligated to.

In Delta Green, the DM is obliged to care by the consensus that we’re all playing Delta Green. The rules have it right there in the system. You could home-brew it into Ravenloft, or simply come to an agreement at the table that you want your relationships with other NPCs to matter in such a way that they get regularly included in the story of course. If you do that though, you’ve built consensus around that point of contention (how much will my character’s relationships come into play) because it matters to you and your table!

More importantly I think, you can turn that on its head when picking systems. If you care about character stories and arcs, you might be well served by a system that mechanizes character stories and arcs somewhat (e.g. Cypher and its derivatives). If you care about court intrigue and NPC & Player interactions, pick something with a well defined social combat system. If you want long perilous journeys to be center in your campaign, pick a system that handles travel and provisioning well.

Or don’t, you can always build consensus in the group about how to handle those things outside of the rules of the base system. Just recognize that you’re agreeing, as an individual and a group, to put in extra effort to come to the agreement.

Consensus Building Can Interrupt or Slow Down Play

More interestingly to me, resolving contention and building consensus can slow down and limit play. If you look at the play flow diagrams in the rest of this essay, you’ll notice we’ve used two different shapes for the elements. Diamonds are used to represent places where contention exists and consensus must be built among the larger play groups:

- Building modules for competitive play and living worlds

- Scoring competitive play

- Updating canon for living worlds and world state for west marches campaigns

These points of contention bottleneck our play. We’re taken out of the main flow of play in order to build consensus before we can proceed with the meat of the game once more. This is really interesting for two reasons. First, identifying points of contention and pre-resolving them via rules keeps us in flow longer. The faster you can get to a resolution on a player’s actions, the more engaged with the game the whole table will be.

As to the second point, let’s look at the three group-of-groups play games above. You’ll notice that in each there are three parallel tracks representing an arbitrary number of groups playing a subgame of the grand game in parallel. The competition groups are running a module for high score, the living world groups are running a copy of the module to ‘vote’ on the new canon, and the west marches players are updating a small portion of the world that they currently have ‘dibs’ on.

In each case a whole group of people is able to act independently knowing that there are rules for building consensus awaiting them after some scoped portion of play. If you’ve ever felt like a game hasn’t gone fast enough for your tastes, or you’re waiting around for it to be your turn, or you’re unable to play as many games as you would like because you can’t get the scheduling to work out, that’s an interesting observation. Contention and consensus building is a lens you can use to introduce larger segments of asynchronous or parallel play to your games, followed by pauses where consensus about what happened in the game is built. The above examples use asynchronous group play followed by group-of-groups consensus building, but there’s nothing specific to that structure about this idea. It should be just as possible to build rules around individual players acting asynchronously and building group consensus at certain fixed points.

Why Does This Matter?

It doesn’t really, but games are fun, and so is talking and arguing about them. In the context of why it matters to play, I like consensus and contention as a lens. It seems to be consistent with the hobby at many levels: convention play, individual tables, solo play, interacting with the community at large. The idea that contention exists around the things that matter, and picking rulesets that provide arbitration (that you like) for those points of contention is a nice tool for selecting systems.

Finally consensus and contention is a very play-flow-focused way of talking about games. For years I’ve struggled with long delays between games, between turns at the table, or between messages in play-by-post settings. I’m interested in finding or building systems of play that allow for more parallel player agency so that everyone has something to do as often as possible at the table. I’m hopeful that different, more concrete language around the flow and bottlenecks helps us have more fruitful thoughts and conversations about those issues, resulting in better systems.